Nosferatu (2024) is a visual Gothic masterpiece, destined to go down in cinema history as the definitive adaptation of the Old World vampire myth brought to life on the big screen.

Paying homage to F. W. Murnau and Henrik Galeen’s 1922 silent classic, director Robert Eggers masterfully weaves Gothic imagery—shadow, blood, and the haunting weight of history—while expanding upon its foundations to align more closely with classic vampire archetypes. The result is a film that not only honors its predecessor but also deepens and enriches the legend of Nosferatu for a modern audience.

There’s a lot to unpack with this one, so let’s dive into my initial review and impressions before exploring the film’s greater thematic context within the Gothic horror tradition.

The Review

Nosferatu (2024) had a slow start, which initially gave me pause. I’d heard conflicting opinions from reviewers I respect and friends alike—those who loved the film really loved it, while those who didn’t, outright hated it.

Having now sat through its impressive two-hour and twelve-minute runtime, I can see why this rendition of Nosferatu isn’t for everyone.

Count Orlok in Nosferatu is not the kind of vampire modern audiences may expect, especially those raised on The Vampire Diaries, Twilight, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, or Interview with the Vampire. He is no brooding, glamorous immortal—he is a decrepit, rotting creature, covered in filth, trailed by an unholy plague that spreads in his wake, heralded by swarms of vermin. His presence is death.

Yet despite his grotesque form, Eggers still manages to pull the erotic and romantic essence of Gothic horror into the film. The story blends themes of addiction, Old World superstition, New World skepticism, self-sacrifice, and the recognition of darkness—both external and within.

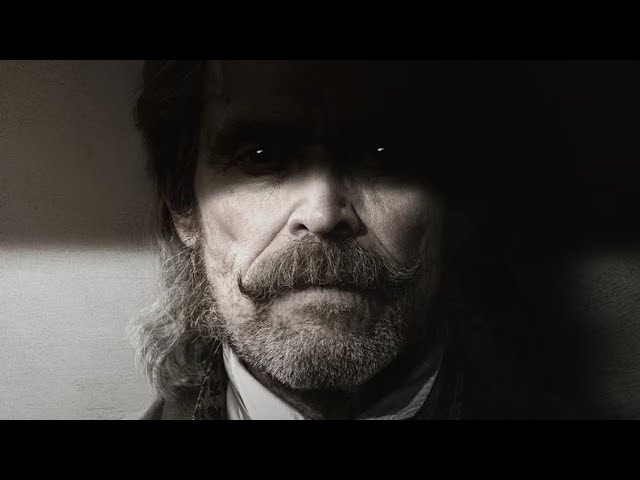

From the sweeping Gothic strings of its haunting score to mesmerizing performances—especially from the ever-incredible Willem Dafoe—Nosferatu (2024) does not disappoint.

I also have to take a moment to highlight the film’s masterful use of shadows and perspective. Eggers uses light and darkness not just as aesthetic choices but as narrative tools. Some of the most striking moments play out in shadows, telling the story in ways that feel both classic and innovative. One unforgettable scene shows Orlok’s clawed hand stretching over the city like a monstrous omen, hunting his prey. Another, near the film’s conclusion, features Dafoe’s Professor Eberhart gazing into the sun, his reflection visible in the mirror—a subtle but powerful visual moment.

TL;DR:

If you can get through the deliberately slow-burning first thirty minutes, the film more than rewards your patience, both narratively and artistically.

I don’t usually give 10/10 ratings because that implies perfection—a standard no film can truly meet. But in this case, Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu comes as close as possible to cinematic mastery. It’s a haunting, visually breathtaking, and thematically rich experience.

SCORE: 10/10 — Not for the Faint of Heart

P.S. – Willem Dafoe was born for this role. He so perfectly embodied the slightly mad yet courageous and philosophical Professor Albin Eberhart that I often found myself enthralled by his performance alone. The moment Dafoe appeared on screen, I was hooked.

I’ve always admired Dafoe as an actor, particularly when he’s given the freedom to explore non-standard, deeply layered characters—his work in The Lighthouse is a prime example. But I must say, hats off, Mr. Dafoe—this might just be the best performance of your career.

Context, History & Analysis

Plagiarism or Transformation?

To do this analysis justice, some background context is necessary. Nosferatu, originally titled Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror, was released as a silent film in 1922. It was an unabashed and unauthorized adaptation of Dracula, the seminal 1897 novel by Bram Stoker, widely regarded as the father of the vampire genre.

The film’s unauthorized nature was no small matter. After Stoker’s death, his widow, Florence Stoker, sued for copyright infringement, and the court ruled in her favor, ordering all copies of Nosferatu to be destroyed. Fortunately, several prints survived, allowing the film to endure and cement itself as a cornerstone of Gothic horror and vampire cinema.

For those unfamiliar, Dracula by Bram Stoker follows Jonathan Harker, a newly minted solicitor who travels to the Carpathians to broker a real estate deal for a reclusive count seeking to purchase an estate in London. Harker soon discovers the terrifying reality of his host—Dracula is no ordinary nobleman but a vampire. Trapped in the castle, he struggles to escape while Dracula sets sail for London, where he inexplicably fixates on Harker’s fiancée, Mina Murray.

What follows is a tale of horror, intrigue, and resistance. Professor Van Helsing, a man of science and faith, pieces together the truth of Dracula’s affliction. As death and hardship mount, Mina falls under the vampire’s influence, drawn into his grasp. The novel builds toward a climactic journey back to Dracula’s castle, where the heroes make their final stand to vanquish the creature and free Mina from his curse. In the end, good triumphs, and all is set right—more or less.

The original Nosferatu follows many of the same story beats as Dracula. Thomas Hutter, a young real estate agent in Germany, is sent by his employer, Herr Knock, to meet the reclusive Count Orlok at his castle in Transylvania. There, Hutter gradually uncovers Orlok’s horrifying secret—he is a vampire. Before he can escape, he falls victim to Orlok’s hunger, though he manages to survive. Weakened, he takes time to recover before making his way home.

Meanwhile, Orlok, having seen a picture of Hutter’s wife, Ellen, becomes infatuated with her. Though there are subtle romantic undertones to his obsession, his desire is primarily framed as an insatiable thirst for her blood.

By the time Hutter returns, a plague has overtaken London, with death on every corner. His employer, Knock, has descended into madness and is revealed to be in service to Orlok. As in Dracula, an eccentric professor enters the scene, and Hutter, along with his allies, bands together to take the fight directly to Orlok in his Gothic abode.

This is where the two stories sharply diverge. In Dracula, Mina joins the men in their journey to the Count’s castle, and they ultimately prevail in their hunt. Through sheer determination, courage, and the strength of their combined efforts, they manage to confront Dracula, stake him, ending his reign of terror.

Nosferatu takes a darker, more tragic turn. While Hutter and his companions set out to confront Orlok, Ellen—Hutter’s wife—takes a desperate, sacrificial approach. She calls out to Orlok, luring him into her home. Offering herself as bait, she distracts the vampire with the gift of her beauty and blood, keeping him occupied until dawn. With the morning light, Orlok is caught unawares. The rays of the sun destroy the unclean monster, freeing the city from his shadowy grip.

Hutter returns to a bittersweet scene: the city is freed from Orlok’s plague, but Ellen has sacrificed her life in the process. As she dies in Hutter’s arms, Nosferatu concludes with a Pyrrhic victory—Orlok is destroyed, and the plague is lifted, but the toll is steep. Hutter is left with the devastation of losing his beloved, and the city remains haunted by the sorrow of what transpired.

While there are key differences—along with various character changes and omissions—the overall structure of Nosferatu closely mirrors that of Dracula. Given these similarities, it’s easy to see why Florence Stoker viewed the film as blatant plagiarism.

I can’t fault Florence Stoker for taking action, but I’m ultimately glad her efforts to erase Nosferatu were unsuccessful. In my opinion, Nosferatu is the stronger, more character-driven work—one that explores complex emotions and more fully embodies the Gothic genre. It’s ironic, considering that Bram Stoker himself is seen as one of the genre’s patriarchs.

What Sets Nosferatu (2024) Apart?

The Nosferatu (2024) adaptation remains faithful to the structure and core events of the 1922 film but significantly expands on characterization. Every member of the cast is given far more depth, allowing for richer emotional nuance. The addition of spoken dialogue further enhances the film’s immersive quality, making the characters feel more tangible while still retaining the grand, larger-than-life presence essential to Gothic storytelling.

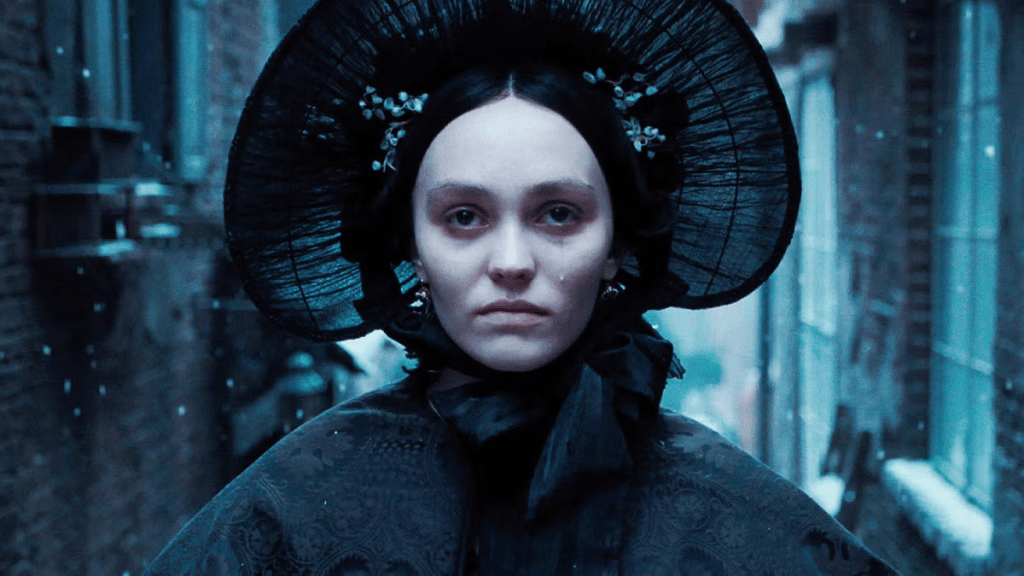

The most striking expansion—and what elevates the 2024 film to a higher level, in my view—is the relationship between Ellen and Count Orlok. In this version, Orlok’s fixation on Ellen isn’t born from a chance glimpse of her photograph, nor is it a simple case of vampiric hunger. Instead, Ellen has been connected to the vampire for most of her life.

From childhood, Ellen was different—gifted, or perhaps cursed, with supernatural abilities that set her apart. She could hear things others couldn’t, see glimpses of the future, and know things she had no way of knowing. These powers left her vulnerable, leading to years of isolation, hallucinations, and creeping insanity. In her desperation, she reached out—and Orlok answered. What followed was a dark and manipulative relationship, built on need, control, and twisted desire—both for blood and for the body.

But Orlok, being a creature of death, was incapable of true love. His connection to Ellen was not affection, but hunger and addiction. She eventually escaped his web when she met Thomas Hutter. With Hutter’s love, the voices and visions faded, and for a time, Ellen was free.

Orlok did not pursue her—at least, not immediately. But when he discovered that she had married another, he flew into a jealous rage. Determined to reclaim her, he orchestrated Hutter’s journey to his distant castle, ensuring he would be far away while Orlok came for Ellen, seeking to seduce her into forsaking her vows and surrendering herself to him once more.

In the end, Ellen did exactly that—welcoming Orlok into her home, submitting to him in a deeply charged encounter. They kissed, and though the film leaves some ambiguity, it strongly implies they consummated their connection as Orlok drank his fill of her.

Yet, just like in the original, this was a ruse. Ellen had lured him in to destroy him. As dawn broke, the sun’s rays sealed Orlok’s fate. But unlike the 1922 film, his death is rendered as almost tender—Ellen cradles him as he withers away, her own life draining alongside his. In the final moments, Ellen and Orlok lie entwined on her marriage bed, together in death, leaving behind a haunting, tragic conclusion.

This focus on addiction, love, hunger, and lust—interwoven into a grotesque yet macabrely beautiful ending—is emblematic of both the vampire and gothic genres. These stories are deeply introspective, fixated on the psychological traumas of the past and how they collide with the present, as well as the societal changes that create friction within the human mind.

I would almost categorize Nosferatu (2024) as a romance—though a deeply disturbing and macabre one, filled with toxicity and self-destruction. It speaks to a universal struggle, reflecting the experiences of those trapped in harmful relationships, torn between attraction and revulsion, unable to break free from something—or someone—that both sustains and destroys them.

A prevailing theme in the film is self-acceptance. Ellen could only defeat Orlok once she acknowledged her dark attraction to him and confronted the parts of herself she wished to keep buried, often arguing against loved ones to be heard and believed. The film suggests that only through this reckoning can one truly be free.

It’s also packed with phenomenal dialogue, much of it delivered by the ever-brilliant Willem Dafoe as Professor Albin Eberhart—Nosferatu’s more occult-minded, and undeniably mad, version of Professor Van Helsing.

“We must know evil to be able to destroy it. We must discover it within ourselves, and when we have, we must crucify the evil within us—or there is no salvation.”

These were among Eberhart’s final words to Ellen, and they proved true. Only by accepting her darkness—by fully acknowledging the parts of herself she had long denied—could she confront Orlok. And in welcoming him into her home and bed, she ensured their mutual destruction.

There was a prior Nosferatu remake in 1979 which, while enjoyable, never quite found its own identity. It attempted to tie itself more closely to Bram Stoker’s Dracula, but in doing so, it lost some of what made Nosferatu unique. It aimed high but never quite reached the heights of either the original film or the novel it sought to emulate.

Nosferatu (2024) took a different approach. Rather than trying to merge its identity with Dracula, it remained faithful to Murnau’s silent masterpiece while expanding and elevating the source material in ways that make it feel fresh, powerful, and deeply resonant.

This is exactly the kind of film I want to see more of. For me, it stands alongside AMC’s Interview with the Vampire, Midnight Mass, and the original Dracula as an essential experience for lovers of Gothic horror and vampire fiction.

Thanks for reading my article! If you enjoyed this review and analysis, please drop a comment, a like, or even better, share it with your friends.

See you next time!

Find me on BlueSky @arkainin.bsky.social